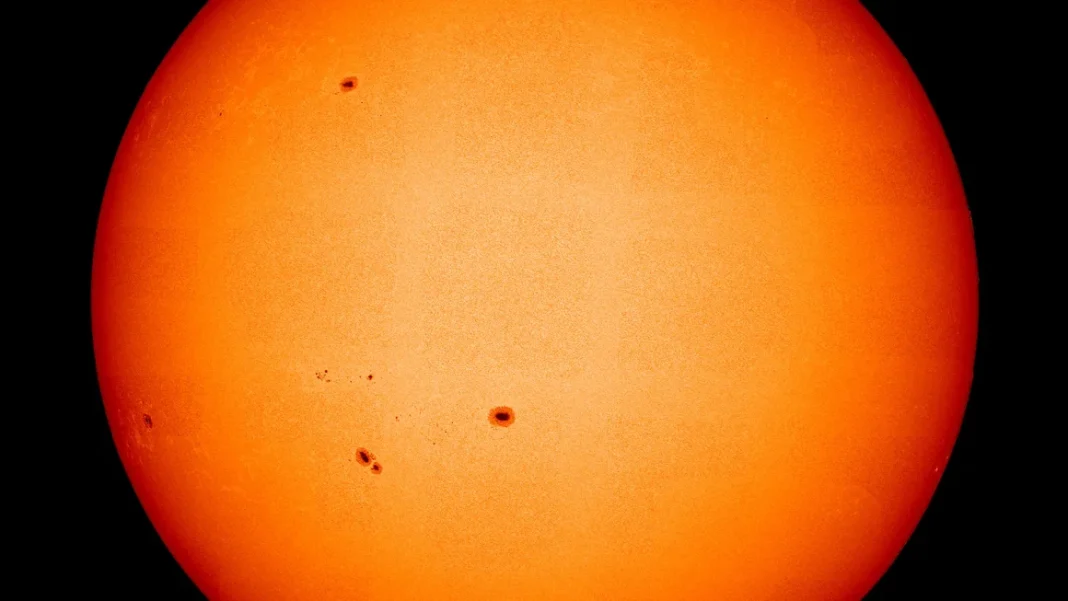

New images of the sun captured by the Solar Orbiter mission showcase the highest-resolution views of our star’s visible surface ever seen, revealing sunspots and continuously moving charged gas called plasma. The images could provide heliophysicists with new clues to help unlock the secrets of the sun like never before.

The images, taken on March 22, 2023, and released Wednesday, showcase different dynamic aspects of the sun, including the movements of its magnetic field and the glow of the ultrahot solar corona, or outer atmosphere.

The spacecraft relied on two of its six imaging instruments, including the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager, or EUI, and Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager, or PHI, to capture the images from 46 million miles (74 million kilometers) away.

The Solar Orbiter, a joint mission between the European Space Agency and NASA that launched in February 2020, orbits the sun from an average distance of 26 million miles (42 million kilometers). Missions like Solar Orbiter and NASA’s Parker Solar Probe are helping to answer key questions about the golden orb, such as what fuels its stream of charged particles called the solar wind and why the corona is so much hotter than the sun’s surface.

Parker Solar Probe is poised to make the closest approach to the sun attempted by a spacecraft in late December, while Solar Orbiter is tasked with taking the closest-ever images of the sun’s surface. The flight path of the Parker Solar Probe will take it too close to the sun to carry cameras and telescopes, but Solar Orbiter is outfitted with an array of instruments to share its unique observations of the sun.

“The Sun’s magnetic field is key to understanding the dynamic nature of our home star from the smallest to the largest scales,” said Daniel Müller, Solar Orbiter’s project scientist, in a statement.

“These new high-resolution maps from Solar Orbiter’s PHI instrument show the beauty of the Sun’s surface magnetic field and flows in great detail. At the same time, they are crucial for inferring the magnetic field in the Sun’s hot corona, which our EUI instrument is imaging.”

Stunning solar portraits

Together, the new images showcase the sun’s varied and complex layers.

The Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager took the highest-resolution full views of the sun’s visible surface, or photosphere, to date. Nearly all radiation from the sun originates from the photosphere, with sizzling temperatures ranging between 8,132 and 10,832 degrees Fahrenheit (4,500 and 6,000 degrees Celsius).

Rippling beneath the photosphere layer is hot plasma that shifts around in the sun’s convection zone, similar to how hot magma moves within Earth’s mantle.

The PHI instrument’s purpose is to map the brightness of the photosphere and measure the speed and direction of the sun’s magnetic fields.

The visible light image of the photosphere showcases sunspots, which resemble holes on the solar surface. These dark regions, some of which can reach the size of Earth or larger, are driven by the sun’s strong and constantly shifting magnetic fields. The spots, regions where the sun’s magnetic field breaks through the surface, are cooler than their surroundings and give off less light.